by Rick Waines, British Columbia

In 1983 I was 17 and attended my first WFH meeting in Stockholm, Sweden, and at the opening plenary Dr. Bruce Evatt stepped up to the dais and pulled the microphone closer to his mouth. I have a recording of his speech which I asked for decades later. I expected to hear gasps from the audience. All I heard was the creak of the microphone as he adjusted it – and his calm voice. What he was there to tell us was that the hemophilia population may be – “a next group” after men who have sex with men to be affected by AIDS. He used the term homosexual which I have not, as it has fallen out of fashion. There was no virus identified yet. He characterized the disease AIDS as – fairly deadly – with very little survival past 25 months. Thus began, by necessity, although I didn’t know it at the time, my interest in memorial art. I had already been diagnosed with hepatitis C but it would be four years before I was diagnosed with HIV in June of 87.

In the inherited bleeding disorder community, we have had our share of experiences with loss, and we continue to face them to this day. Access to life-saving clotting agents is not universal and the impact of bloodborne pathogens are well established. For me an important question is, how have we born witness to this loss, and how can we strengthen our efforts to remember. Or, how can we deepen our understanding of our past with an eye toward healing. And finally, what role does a practice like memorial art have in helping to prevent future calamity. And what the heck is memorial art anyway.

I would like to point out that I am not an expert in memorial art. I have come to this topic due to a piece of documentary theatre I have created, based on an oral history project called “HIV In My Day.” Creating a Verbatim Drama has put me in the role of caretaker of a history, and the stories of those lost along the way. As I understood it to be a work of memorial, I wanted to understand the history of memorial in the arts.

It is important that my play does more than simply keep us from forgetting – “not forgetting is insufficient” – Ted Kerr. This quote comes from an article by Ted wrote for C magazine – How to Have an AIDS Memorial in an Epidemic. Throughout this article and in my work with In My Day, I have relied heavily on his insights on memorial art and AIDS. James E Young’s – Reflections on memorial Art, Loss and the Spaces In-between has also been an important guide.

From “How to Have an AIDS Memorial in an Epidemic” C magazine by Ted Kerr – Photo credit by National Institutes of Health – Wikipedia

Memorials have likely been with us as long as we have experienced loss, but it was after World War I that memorial art really took off. This period of memorial is represented by monumental expressions by the state. Meant to remember, yes, but also to represent a resiliency through towering structure.

Menin Gate Memorial to the Missing, in Belgium. Tijl Capoen/VDB – Credit: VDB

World War I War Memorial in Cernobbio, Italy.

These memorials are typically political, have strong national overtones, and also use religious imagery.

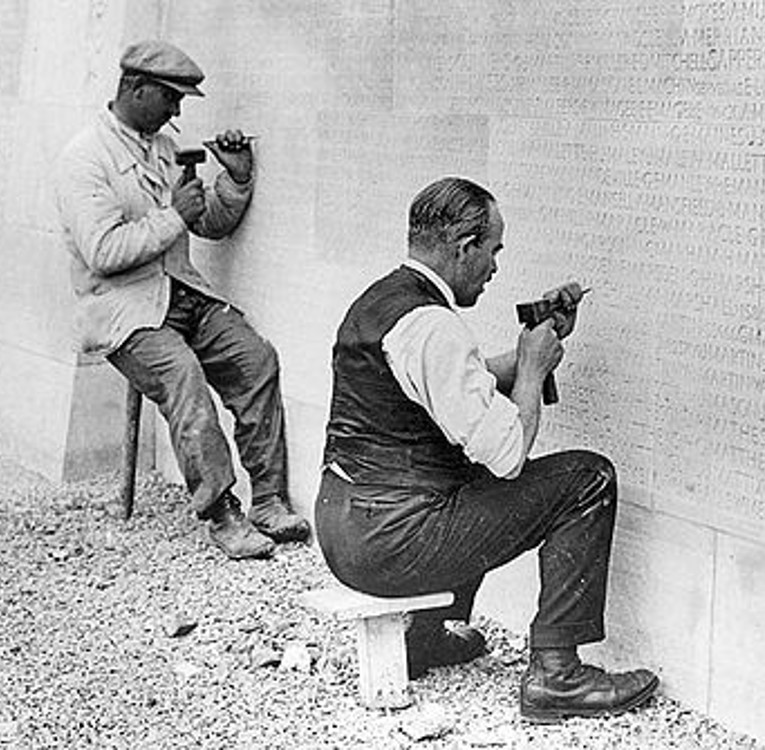

There did exist some innovation in these first memorials of the 20th century, best exemplified by the practice of including the names of the dead, countering the practice of the heroic general on horseback.

Carving the names into the Canadian National Vimy Memorial.

At the conclusion of World War II we became aware of the horrors of the Holocaust and a new kind of remembering would need to be employed. There was an understanding that any attempt to memorialize would risk a kind of redeeming of the suffering, or a healing of these horrific acts where there was no redeeming or healing that would be sufficient. The arts can soothe with beauty where there is none, at all, and this needed to be guarded against.

So how did memorial art change in the face of this challenge? In Germany where debate about how to memorialize was most fierce, James E Young, an academic who was hired to lead the process insisted that the architectural elements envelop the visitor, rather than tower over and overwhelm, and that monuments should also contain learning centres where deeper understanding of the Holocaust could be the goal. What we see in this period of memorial is a centering of humanity, a refusal of the instinct to fill the void left by horror and deep trauma. If you have visited Peter Eisenman’s Field of Stelae or Monument to the Murdered Jews of Europe as it is also known, I think you will agree that it has an extraordinary impact and invites one in supporting deeper enquiry.

Peter Eisenman’s Field of Stelae, in Berlin. – Photo credit: The AdvenTourist

Today, memorialization efforts are moving toward building meaning through the memories of survivors, or stories of the dead told by the living. However, there will always be a place for a more enumerative approach or what author Dagmawi Woubshet calls – the trope of inventory taking.

In Vancouver, we have a memorial wall dedicated to those lost to AIDS. It is located, interestingly, next to a famous site where gay men still cruise to this day. This memorial remains an important place to go to remember the losses generally, but also to honour individuals you may know yourself. It is personal in that way.

But it is this memorial itself that shines a light on where our community has perhaps some work to do. Instead of the names of people with bleeding disorders being included, there is a more general acknowledgment of our loss with an inscription that reads — members of the Canadian Hemophilia Society – or something like that. This inscription stands out amongst the hundreds of names – of people – not a non-profit representing people.

AIDS presents different set of challenges than WWI and WWII. There is not yet an end to the AIDS crisis, and successful memorials to the losses associated with the AIDS pandemic recognize this. The Texas AIDS memorial garden, for example, must be tended.

Reminding us that the work is not done, it is never done.

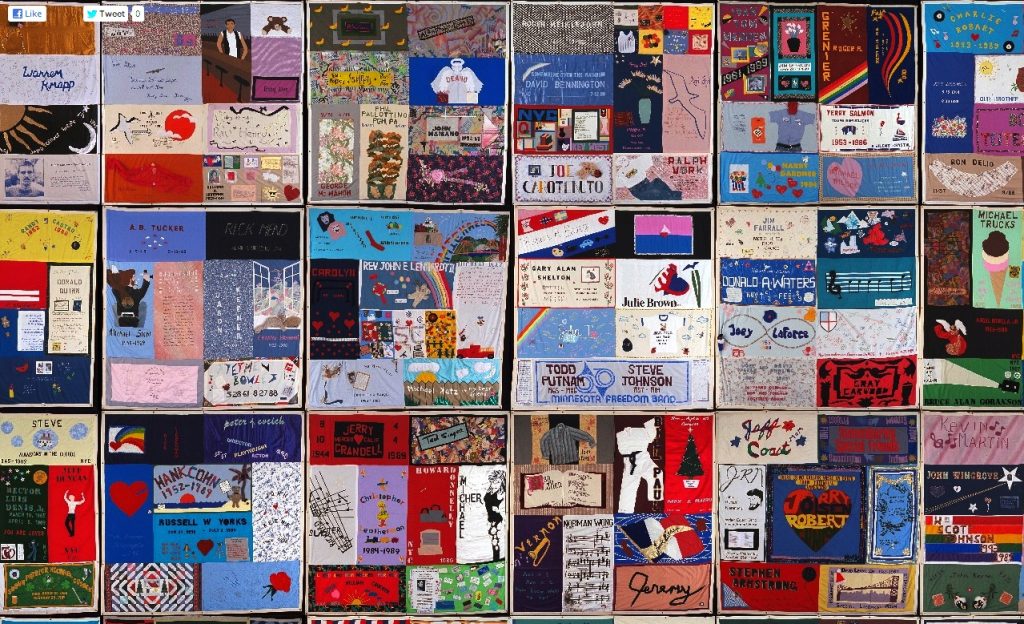

The Names Project, conceived in 1985 by Cleve Jones, now features 48,000 panels remembering over 90,000 people. Each panel, more than a name to count, tells us something about the person and is a living memorial with new panels being made today, while I speak perhaps, at a workshop, or at a sewing machine of a loved one. These modern iterations of the memorial allow us to build more complete and complex understandings of lives lost, lives lived.

Explore All 48,000 Panels of the AIDS Memorial Quilt Online – www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/aids-memorial-quilt-now-online-180975370/

This brings me back to our community, the bleeding disorder community, and our efforts to memorialize those we have lost. In the U.S., there is the Hemophilia Circle at the National AIDS Memorial, where 200 names or so of people from the hemophilia community who have been touched by AIDS are engraved on a stone wall. In the United Kingdom on each thanksgiving there is a service at St Botolph’s Without Bishopsgate in London. There is a book of remembrance at this event where the first names of those lost are read. In Canada, we have a national Commemoration where a tree is planted and accompanied by a plaque that speaks to our loss. These acts of memorial hold an important place, but I can’t help but wonder whether we might benefit from the addition of more personal approaches. Some examples have begun to emerge in our bleeding disorder community. Rob Cooper’s Unspeakable is masterful in its ability to marry a dramatic, historically accurate retelling of the catastrophe that was the tainted blood scandal in Canada providing importantly an example of successful activism along with lovingly rendered portraits of people with bleeding disorders.

Zander Masser, in his upcoming book Unburying My Father, has undertaken a very personal journey of getting to know his father – who died during the tainted blood crisis – through a very particular lens. And my Verbatim Drama – In My Day – follows survivors and their caregivers through the first 15 years of the AIDS pandemic. Given the verbatim nature of this piece of theatre, we get to know the 118 contributors and those they lost, in their own words.

Each one of these memorials has an important place in the healing our global community continues to wrestle with. What I would also offer is that there is an opportunity we have before us to offer more than the trope of inventory taking. We need more than their names. We need to know them, if only just what their favourite colour or hobby was.

So, let’s remember that memorial art must support our goals of activism, let’s bring the stories of our loved ones to the fight for safe and secure treatment for all.

For more information on In My Day, Unspeakable, and Unburying My Father, please go to the links below.

In My Day – A verbatim drama

KEYWORDS

ADVOCACY ageing A GLOBAL PERSPECTIVE AIDS CARRIERS CHS chapters Community COMPENSATION COVID-19 EMICIZUMAB GENE THERAPY HALF-LIFE FACTOR CONCENTRATES HEMLIBRA HEMOPHILIA A AND B HEPATITIS C HIV ICHIP INHIBITORS MYCBDR NURSING PHYSIOTHERAPY Platelet function disorders PROBE PROPHYLAXIS RARE BLEEDING DISORDERS RESEARCH SOCIAL WORK Tainted blood tragedy THE BLOOD FACTOR THE FEMALE FACTOR THERAPIES THE SAGE PAGE TWINNING VON WILLEBRAND DISEASE

Copyright © 2020 - Canadian Hemophilia Society. All rights reserved.