Results of CHS survey on gene therapy

This past summer, the Canadian Hemophilia Society (CHS) conducted an on-line survey on attitudes to and knowledge about gene therapy. The results were presented and discussed at the CHS Blood Safety and Supply Committee special meeting on gene therapy this autumn in Toronto.

The survey, whose answers were anonymous, was targeted at Canadian residents with severe hemophilia A or B, fourteen years of age or older, who represent the patient group that might consider taking gene therapy in the next five years.

The survey was publicized via the usual via CHS communication channels: website, CHS CONTACT, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and some chapters’ social media, and was available in both English and French.

Thirty-nine people completed the survey, 31 with hemophilia A, seven with hemophilia B and one not specified. This accurately reflects the prevalence of severe hemophilia A and B in the population.

Fifty-four percent (54%) indicated they thought they would be eligible for gene therapy, 28% thought they would not be eligible and 18% said they didn’t know. Reasons for thinking themselves to be ineligible included a past history of inhibitors, pre-existing antibodies to the AAV vector used to deliver the gene for factor VIII or IX, age (under 18 or over 75) and other medical conditions, for example active liver disease.

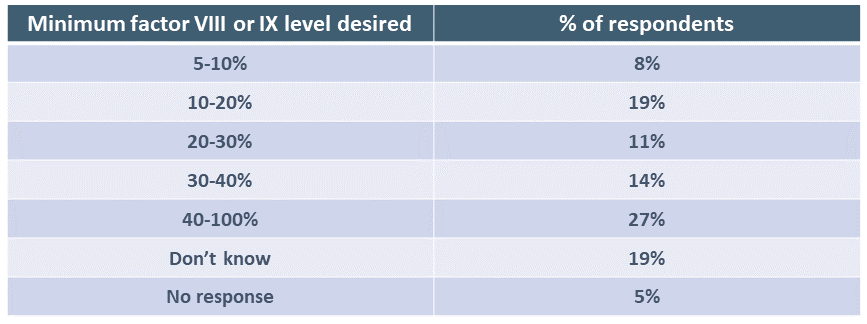

Respondents were asked the minimum level of factor VIII or IX expression predicted to be achieved that would make them want to have gene therapy. Answers varied widely.

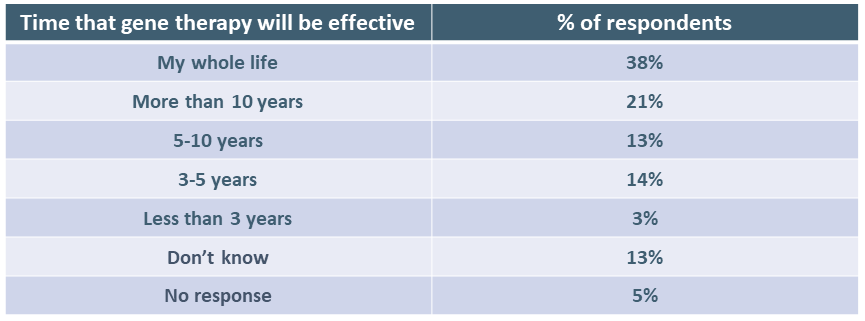

Respondents were also asked how long they would expect the factor level they chose in the question above to last for them to accept gene therapy. Again, answers varied widely, which is not surprising given that clinical trials for hemophilia gene therapy have provided no clear answer to this question. It is worth noting that 6 out of 10 respondents (59%) indicated they expected gene therapy to be effective in preventing bleeding for at least 10 years. Clinical trial results in hemophilia A, however, point to a shorter period in which patients would have a “treatment break.”

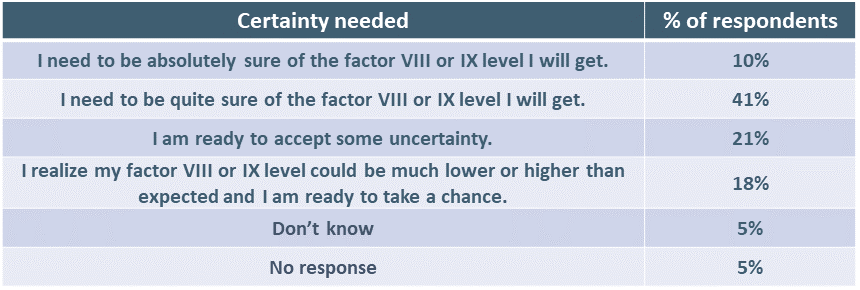

Respondents were asked how much certainty they needed as to the factor VIII or IX level they might achieve. Five out of 10 (51%) need to be quite sure or absolutely sure of the eventual factor level obtained. Unfortunately, clinical trial results show a highly variable and unpredictable level of response from individual to individual, ranging from no response at all to levels above normal.

Respondents were asked if they would accept gene therapy if they were told in advance that steroids would probably be needed in the period following administration. Forty-one percent (41%) said yes, 18% said no, 36% didn’t know and 5% had no response. Many respondents commented that this was an important factor that would cause them to pause. Many others indicated they needed more information on this subject.

The survey asked if people would accept to receive gene therapy knowing that that there would be frequent blood draws in the weeks and months following administration, and they would need to be followed up in a registry for 10 to 20 years. Sixty-four percent (64%) answered yes, 13% answered no, 18% didn’t know and 5% gave no response.

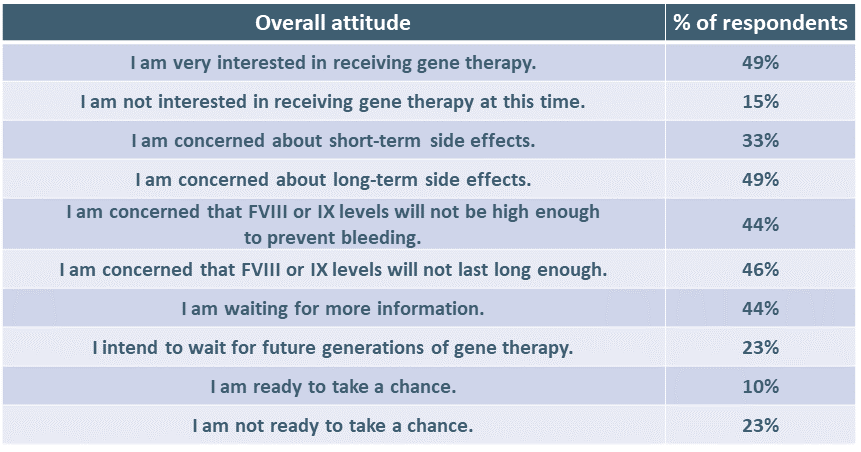

Respondents were asked to express their overall attitude to gene therapy. (More than one answer was allowed.)

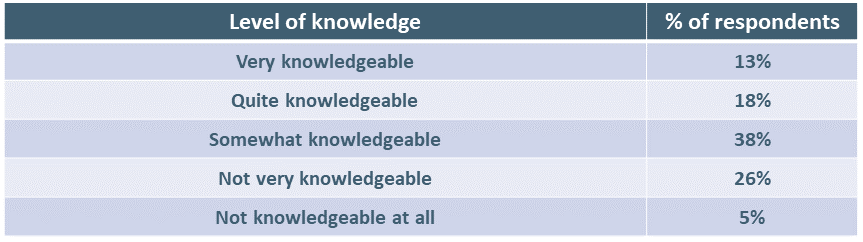

We asked respondents to indicate how knowledgeable they felt themselves to be.

Respondents also indicated what they would like to know more about. Answers were:

- Everything.

- I just wouldn’t do it.

- Nothing, I trust the science. I just want it.

- How the therapy can be improved to provide better and more consistent results.

- How to avoid the exclusion of those with HIV and/or HCV infection.

- The complete working of it.

- The experiences of those who have gone through the process.

- Why and how it lasts for the amount of time that it does.

- More about side effects.

- If additional doses are possible if my levels drop, especially with future generations of gene therapy.

- How it’s being developed safely and securely.

- Side effects, long term effectiveness.

- Parallel information from other gene therapies for other disorders.

- Trough levels, duration of levels, risks.

- Cognitive/neurological risks.

- Risks of comorbidities.

- Will government be inclined to pay for gene therapy?

- The kinds of support that would be available to a person in the first few weeks and months when there are numerous blood draws and appointments with medical personnel.

- The lasting effects for those who went through clinical trials and received corticosteroids.

- If I don’t respond, can I go back to my previous treatment with factor?

- The long-term risks.

Gene therapies for hemophilia A and B have been approved for use in Europe and the U.S. We can expect submissions to Health Canada in the first half of 2023. Gene therapy for hemophilia B could be available in Canada as early as 2024 and for hemophilia A in subsequent years.

Our community has a huge challenge in increasing knowledge and awareness about these very different, one-time treatments. Informed and shared decision-making among patients and clinicians will be critical as these therapies become available.

The CHS would like to thank those who took the time to respond to the survey. Your feedback is extremely helpful as we design community education and awareness programs.