The bleeder wore white

For those who follow fashion trends, you know that white dresses are trending this spring. It was easy for me to find one that suited my needs. Business casual: check. Linen: check. Short sleeved: check. Midi length: check. Packable: sort of.

You see I was asked to speak at the Women and Girls with Bleeding Disorders Workshop: Heavy Menstrual Bleeding, during the WFH 2024 World Congress in Madrid. White was right.

The topic assigned to me was Interprofessional Communication. Fifteen minutes. Fifteen minutes to share my forty years of learning and experience as a nurse added to another decade (or so) as a patient relying on that communication. I checked the enrolment before I started my PowerPoint and was extremely pleased to discover that most attendees were nurses and physicians. It was not nearly enough time to teach them all that I needed them to learn, but it was my opportunity to get started. I also knew that there was lots of data to back up my messages.

I broke the presentation into four parts. I started with the science, looking to the Canadian Interprofessional Health Collaborative: Competency Guidelines to review the essentials in health communications. I emphasized the importance of respectful, explicit, clear language in written, verbal, and non-verbal communications.

Moving on, I talked about what I hoped may be a new concept called a structured briefing protocol that might be adopted by a team to improve communications, especially in an emergency. Coincidently (I am writing this while Alberta is evacuating communities as fires blaze), one of the examples I used came from the US Forest Service, who uses STICC. It is essential to share critical information, using these points: situation, task, intent, concern, and calibrate. It is easy to draw comparisons between the Forest Service responding quickly and effectively to save lives with the ever-changing variables during a fire and a hematologist responding to a call for help from Labour and Delivery when a bleeding mother is in danger.

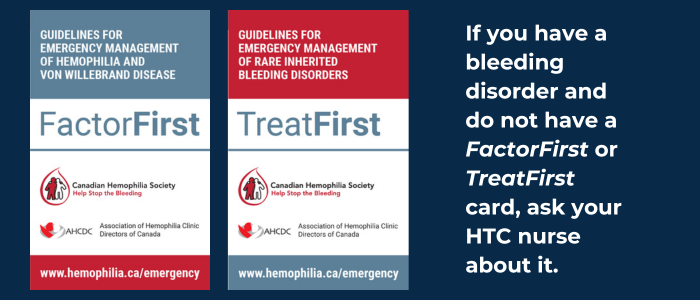

We have a plethora of tools which use the science around interprofessional communication. In addition to cell phones, EMRs, telemedicine, Zoom and so on, we have tools in our wallets and around our necks that deliver essential information from one health care professional to another. These tools have been available and saved lives in Canada for many years: FactorFirst and TreatFirst cards and Medic Alerts bracelets. Importantly, these are recognized as being credible resources. I encouraged the physicians and nurses to make certain that the information is reviewed and edited annually and after any change. I doubt many patients realize that they are simply delivering essential communication from one health care professional to another, but nonetheless have responsibilities related to those resources.

Finally, I spoke about the power in a consultation note. Ideally, with electronic patient records, each member on the care team who is involved has access. I work with a respirologist who teaches our residents and fellows to write an If I should die tonight consultation note. Meaning that the note must be comprehensive. Report the details from an expert perspective. Help others to understand the situation, task, intent, concerns/risks and then calibrate. Remember that note is essential to good patient outcomes.

Those fifteen minutes went fast, at least for me. Noting that I still had several audience members awake and listening, I asked if they had noticed my dress robe – a non-verbal form of communication. My white dress was chosen purposely for my presentation. I told them that as a woman living with a bleeding disorder, from the time I was nine years old until I was in my early forties, I had never worn a white dress, except for my wedding gown.