Unburying My Father: The life and photography of Randy Masser

by Zander Masser, Montreal, QC

On a fall day in 1996, my parents called a family meeting. I was 11 years old. My brother was 14. We were in the living room. I sat on the green pleather couch next to my brother and across from my parents, my mom on the left, and my dad on the right. There was an air of seriousness in the room, which was uncharacteristic for our household, so I knew something was wrong. I thought they were going to tell us that they were getting a divorce. I couldn’t imagine anything worse than that. My mom did most of the talking. They told us that my dad had been HIV positive for over 10 years – my entire life – and that he had AIDS. They told us he had become infected with HIV through his hemophilia treatments. They assured us that my mom, my brother, and me, were not infected. They explained the terminal nature of the disease but tried to sound hopeful about the medical care my dad was receiving at the Mount Sinai Hospital in New York.

After that discussion, I knew that my dad was going to die. I assumed that his death would be very far in the future, and that he’d be an old man by then. I lived in denial even as my dad’s health declined over the following three years. After that family discussion, the topic of my dad’s death was not discussed again until the day he died.

“I am standing on the shore looking out onto the ocean. It isn’t a pristine white sand beach with clear water. It is brown, dark, dirty looking sand and the water dark green. I have a palpable feeling of calmness. It’s sunny, I hear the waves crashing and feel the breeze. Out of the corner of my right eye I see a figure approaching. No face or distinguishable features, just a black silhouette of a person running towards me. Before I can turn to see who it is, this person plunges a knife into my chest. I wake up. It’s about 3:00 a.m. I go back to sleep, and wake up again at 6:00 a.m. and I hear mom talking in hushed tones in the basement. I knew dad had died. I went downstairs. She was on the phone with my grandparents. She hung up promptly and we embraced. I think now that the feeling of tranquility in my dream was one last gift of peace before I woke up into my new reality, before being on the other side of the great focal point of my life.” – Graham Masser, my brother

I didn’t know it at the time, but my grief started on the day of this family meeting. In the years before he died, I gradually grew more worried about him as his physical condition declined. I became protective and I walked slowly next to him, refusing to leave his side. Immediately after he died I was in shock and intensely mourned. I remember being unsure how to continue with my life. As time passed, I lived a fairly “normal” young adult life, but I also settled into a silent acceptance of my dad’s death- which lasted twenty years- during which I spoke to almost nobody about my experience of loss. But my mind churned as I constantly considered the impact of my dad’s death.

Finally, as I entered my thirties, two decades after my dad died, I finally found a way to open up, share my grief, and heal. My healing process took the form of a photographic narrative titled, Unburying My Father.

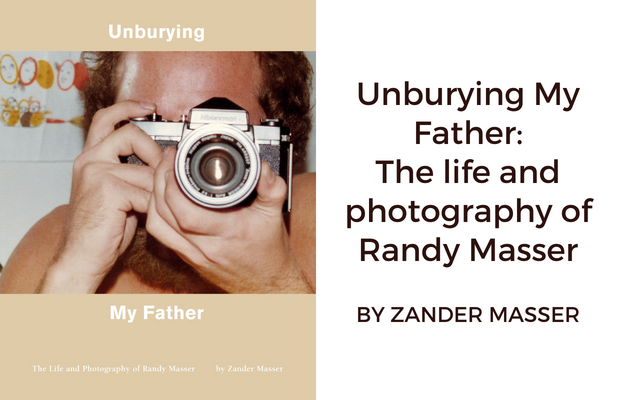

My dad, Randy Masser, lived with severe hemophilia B. He was a professional photographer. I grew up surrounded by his photos on the walls of our home, and when I conjure images of him in my mind, which I do many times a day, it’s hard to imagine him without a camera around his neck.

Several people, including my grandparents, told me that they did not know where my dad’s interest in photography came from. My dad participated in life as much as he could, but because of his physical limitations, he couldn’t fully engage. Akin to having a heightened sense of hearing if you are blind, I think that his observation skills were sharpened by being on the sidelines and watching others move through the world in a way that he was not able to. This translates to the camera lens. I believe that once he picked up a camera, he was naturally skilled at identifying and capturing elements of everyday life in a meaningful and artful way.

Twenty years after my dad died, I unburied his entire photo collection- totalling ten thousand slides. As I scanned and archived each photo, I felt a strong desire to learn more about my father. I reached out to every person I could think of that knew my dad, and I asked them to share their memories with me. And thus, the Unburying My Father concept was born.

The book tells the story of my father’s life through the memories of those that knew him best, and it is illustrated by over two hundred and fifty of his stunning photos. My dad was an immense talent, and a big personality in a small frame.

“My mother died when I was three and my father was absent. My aunt Mary, my mother’s sister, took me into her home. She had two boys with hemophilia. I can remember from my young life, living with my aunt Mary, seeing two boys in bed all the time. At that age I did not know what their illness was, and nobody ever told me that I could be a carrier of hemophilia.” “I used to sit and wait for Randy to come home from school because I was so frightened. The worst week of my life was when he went to Boy Scout camp. The people there knew that he had hemophilia. He had the most wonderful week of his life.” – Eleanor Masser, my dad’s mother.

“When your dad got the results, we went to the hemophilia treatment center at Mt. Sinai. They talked to us about his T cell count, and they gave us some hope in terms of new medications being developed. He didn’t tell people initially because there was a myth that it was very easy to transmit, such as by shaking someone’s hand. We were furious at the pharmaceutical companies, but moreso, we were scared. Scared about what this meant in terms of our, and our sons’, mortality. Once he tested positive, our sex life stopped. I was so terrified of making a mistake in the heat of the moment that I just couldn’t deal with it.” – Ilene Masser, my mother

The process of creating this book has transformed my life in many ways. One of the primary changes is a recent integration into, and loving acceptance from, the hemophilia community. Before delivering the keynote speech at the Hemophilia Federation of America’s symposium last year, I didn’t see myself as part of this community. Since this introduction at the symposium, so many people with bleeding disorders – and the family members, clinicians and others that support them – have graciously reminded me that I am and have always been a member. Being connected in this world has helped me to realize that I was never alone in my experience, even though it felt that way for so long. I have met community members who knew and worked with my dad. I have also talked with people my age whose parents died the same way my dad did. Making these connections has given even more meaning to my dad’s life, my family’s story, and my own work. I am eternally grateful for the warm embrace of the hemophilia community and the platform that many organizations have given me to share my story.

“Randy made friends with people the way a lake reflects the sky. It can’t help it.” – Stephen Cowan, my parents’ friend and my childhood pediatrician

I learned many things about my father through the process of unburying his story. I learned that he was a board member of the Hemophilia Association of New York for over twenty years. He ran support groups for young adults with bleeding disorders and was often asked to counsel individuals and families. His advocacy work was crucial to passing the Ricky Ray Hemophilia Relief Fund Act in the United States. As I continue to engage in the hemophilia world, I feel as though I am continuing my dad’s work with him.

My life has also been transformed as I have discovered how to use creativity to process my grief and live with it in a healthy way. I am now able to share my experience and tell my story. I no longer live in silence. As I collected stories about my father, and placed those stories next to my own, I saw that I was never actually isolated in my grief. I realized that I had always been surrounded by people who also loved and still miss my dad. Now that I understand my father more fully, I can better understand myself, which has made me more confident in who I am. Now that I understand the incredible sacrifices my mother made in her role as my dad’s partner and caregiver, I can work to repair my relationship with her, which was damaged by our grief. I have built compassion and empathy for my parents, and for myself. I have realized that my father’s life has had a much greater impact on me than his death. I have learned the healing power of storytelling. Developing the skills- especially through creativity- to openly share and talk about grief is crucial for growth and mental well-being.

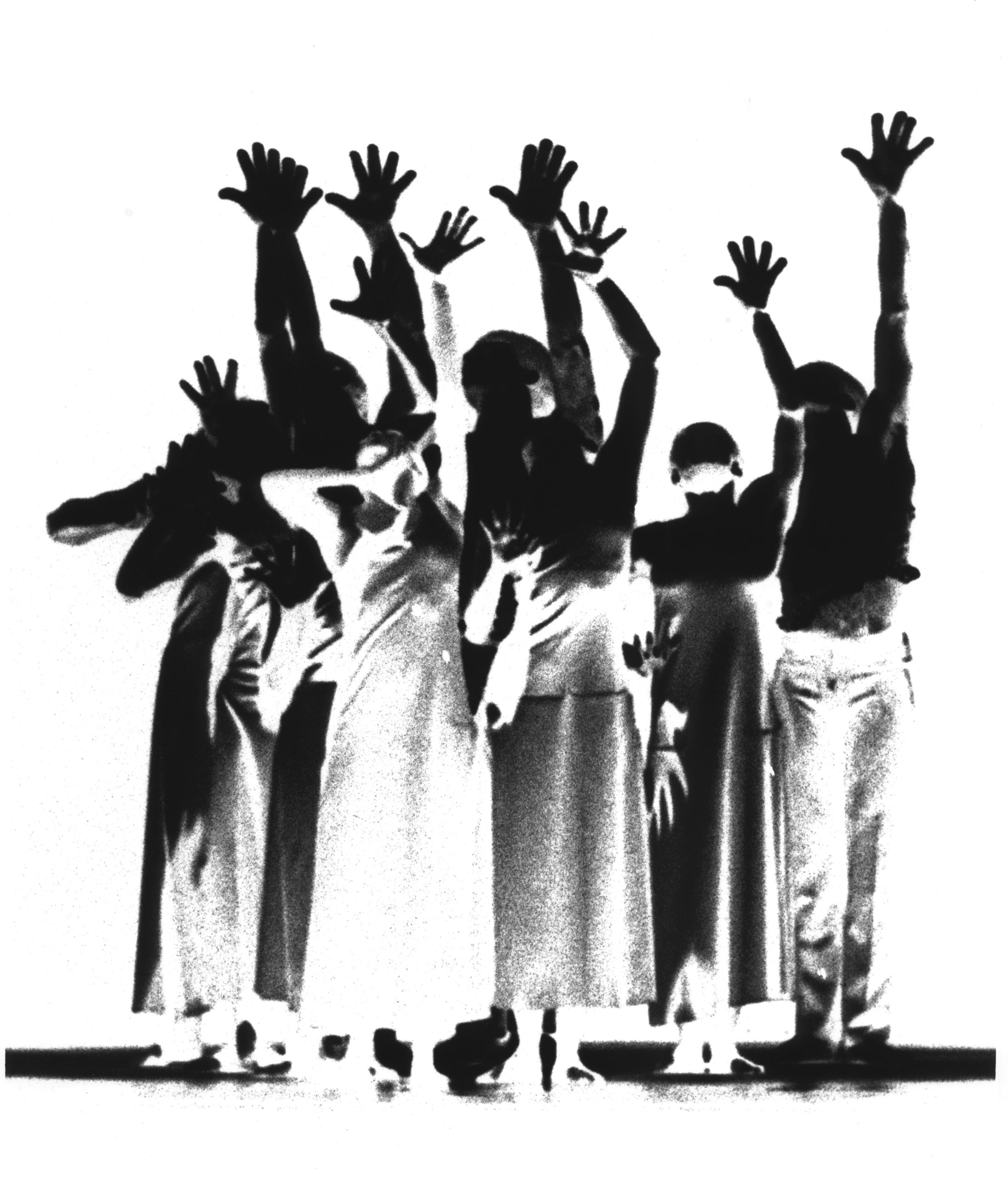

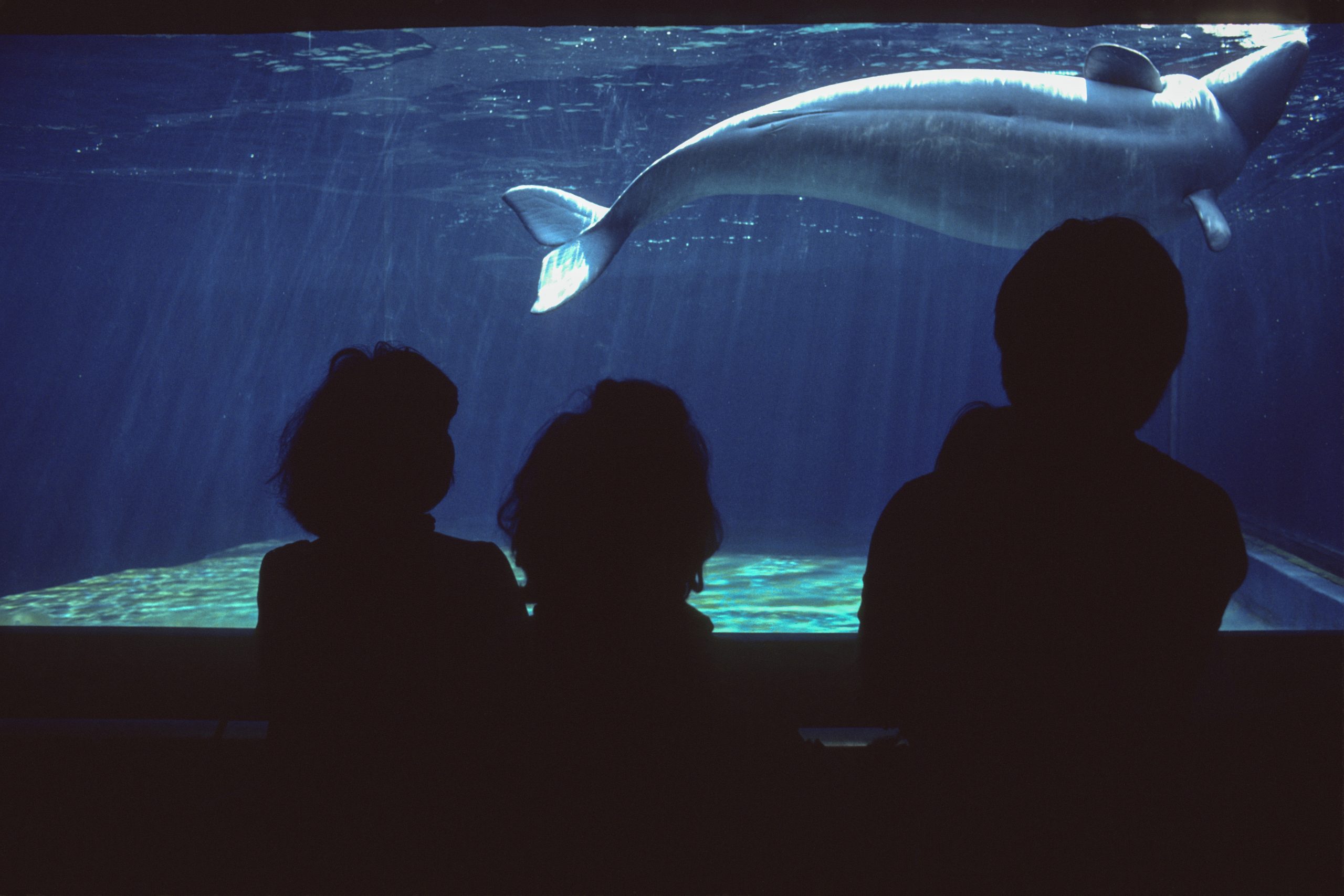

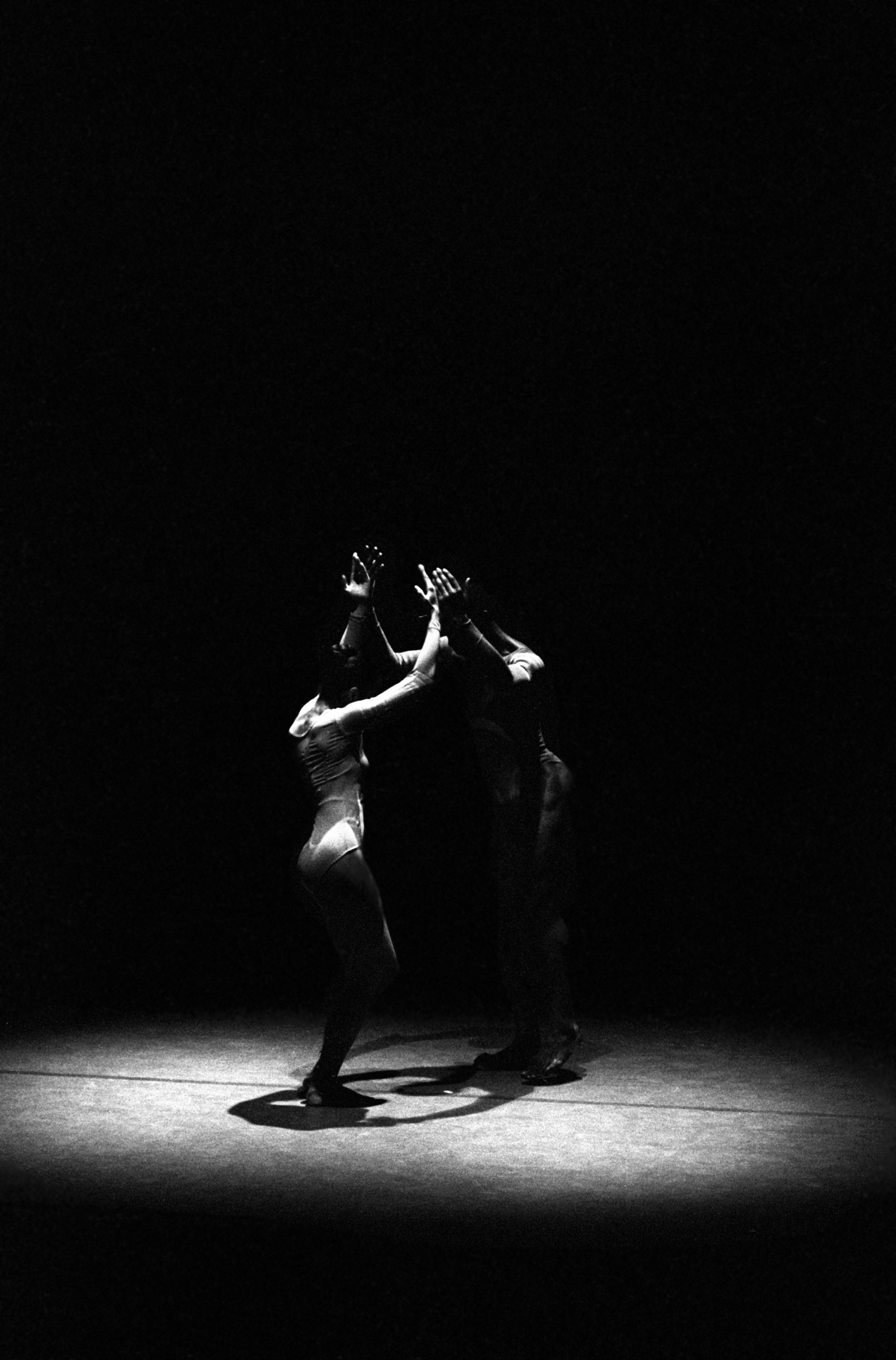

My father channeled his grief into his photography. In his photos, I see and feel so much emotion. I perceive a man who is longing for life and for whom the everyday, mundane moments are precious and beautiful. However, he did not have the space nor the language to talk about his experiences of illness, injustice, and loss of autonomy. And so he remained silent. While my father did not teach me how to talk about heartache, he showed me the value of creative expression, how to prioritize joy, to enjoy art and music, and how to appreciate the gift of just being alive.

“Because of my doctor role, Randy did confide in me about his fears and pains. But he had a kind of nobility in his refusal to go negative about it. He would say, ‘This sucks’ and we would talk about his pain. But he would steer the conversation away from my questions about fear of dying. We both knew he was afraid, but he knew that Ilene was so, so afraid of this unspeakable thing, and he didn’t want there to be fear in the house. He wanted to dilute the fear of dying by staying positive, bringing light and optimism. “One day we watched the one-armed pitcher Jim Abbot pitch a no-hitter for the Yankees. Randy was at his house and I was at mine. We stayed on the phone together for the last three breathtaking innings talking, Randy narrating every pitch. That strange amazing game became my metaphor for Randy’s ability to stay positive through adversity. It’s why I did that painting for him. A one-armed pitcher pitching a no-hitter. That was Randy.” – Stephen C.

Every one of the thousands of lives lost to the tragedies caused by contaminated blood is important, and every impacted family has their own story to tell. My hope is that in reading my book, readers will connect to my family’s story, and be inspired to find ways to confront their own grief and share their experiences with the world.

________________________

Since releasing his book, Unburying My Father, on June 12, 2022, Zander Masser has delivered and curated talks, workshops, and photography exhibits to various hemophilia organizations in the United States and Canada. He was the most recent keynote speaker at the Hemophilia Federation of America’s annual symposium, and he spoke at the World Federation of Hemophilia congress in Montreal.

To learn more about Zander’s work, Randy’s photography, and to purchase the book, you can visit www.randymasserphoto.com. You can also follow Zander on Instagram at @zandermasser where he has shared many aspects about creating the Unburying My Father project. Zander is available to speak at in-person and virtual events. You can reach Zander by e-mail at zander@randymasserphoto.com.

PHOTOS by RANDY MASSER